Story #1: Childhood on a Farm in England in the 1930s

I am 96 years old and have lived in retirement in Kangaroo Valley since 1994. I was born in England in 1929. When I was about 16 months old, my father died in the ‘flu epidemic sweeping Europe at the time and my widowed mother took me home to live at the family farm near Colchester in Essex, about 60 miles (90km) north-east of London. That is where I spent a very happy childhood until I was 9 years of age. Let us explore together what life was like on a small farm such as ours in the 1930s.

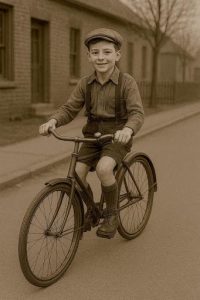

There were lots of loving grown-ups and plenty of cousins living nearby. We had lots of animals. Three dogs, a succession of cats to keep down the rats and mice, some rather smelly white mice at one time, a white rabbit (that later bred with the wild rabbits), a couple of pigs, numerous Rhode Island hens, turkeys to be fattened up for Christmas and a few pet ducks, and always a couple of farm horses. All the humans had bikes, used strictly for transport, not for sport or exercise, as seems to be the case in Kangaroo Valley today. In 1936, when I was seven years old, I used to cycle a mile on my own, to catch the school bus in all weathers. All the roads were paved with asphalt, even the very minor, narrow, twisty lanes, unlike our broad, straight KV roads, many of which were still dirt when we came here to live in 1994. We had no family car in the 1930s. We ate lots of plain farm food which will be described later. There was no plumbing inside the house or out and no electricity. We didn’t have a radio or television or phone, and never a great amount of spare money as we were in the middle of the Great Depression. Computers and mobile phones were way off in the future. Well, that is just how things were in those days.

A 1930s boy with his bicycle

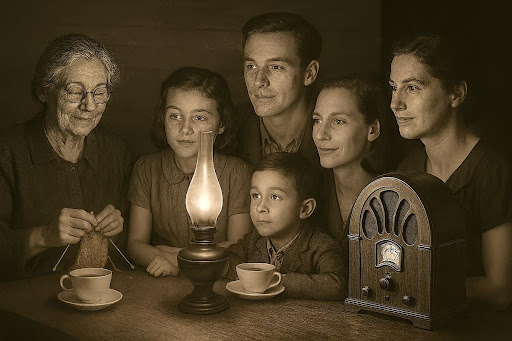

We got our first battery wireless set (radio) in 1935, especially to hear the silver-jubilee speech of King George 5th (King Charles 3rd’s great-grandfather). We were all royalists in those days and strongly supported the monarchy. The wireless set worked with two batteries, a very heavy 6-volt battery called an ‘accumulator’ that was recharged at the railway station once a week and a disposable high-voltage battery that was replaced every few months. We used to sit around the living room table in the evenings to share the light from the single ‘Aladdin’ oil lamp that worked on kerosene.

Mains power came in 1936, when a pylon was built in one of our fields to support a new high-voltage transmission line between neighbouring towns. An electrician wired up our house for lights. Now we could get light merely by clicking a switch instead of carrying a candle to bed. We still had to pump our very hard drinking water by hand from the well outside the kitchen door. Water was carried into the house in buckets and heated in a kettle on the hob by an open fire in the living room. To wash up, one of the grown-ups would carry hot water back to the kitchen. There was no flush toilet. We had a lavatory in a little wooden outhouse (called a privvy in England and a dunny in Australia). Under the seat, there was a very large bucket lined with straw that was emptied once a week. It got a bit smelly close to emptying time. At night, you could use a chamber pot stored under the bed if you needed to pee or poo – that got a bit smelly too!

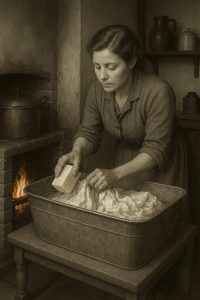

Monday was laundry day regardless of the weather. Bucketfuls of water were tipped into a copper boiler in the kitchen and heated by a coal fire underneath. The clothes were washed by hand with a bar of kitchen soap in a big bath made of galvanised iron and dried on clothes lines in the back meadow. Then the very uneven brick floor of the kitchen was scrubbed on hands and knees using the warm soapy water. There were no household detergents in those days.

A woman washing sheets using hot water and soap

On Monday evenings, everyone had a bath in the kitchen, starting with the children, and all the dirty water was carried outside to a smelly drain emptying into a muddy ditch. The ladies washed their hair in the kitchen sink, using rain water collected from the roof. Tuesday was the day for drying clothes, in front of the living room fire if necessary. Wednesday was ironing day. A flat iron was heated on an open fire in the living room and well wiped to clean off the soot. On Thursday the whole house was cleaned, by hand of course, no vacuum cleaners or other mechanical devices. Housework was very hard work in those days. Friday was shopping day, carrying a basket on the train to the nearest town. Great fun for kids. Saturday was for sport and Sunday for church. More on that later.

Story #2: Food on an English farm in the 1930s

We ate well, with much of the food produced on the farm. Our soil was very fertile and a succession of different kinds of vegetables were grown for sale in the London markets throughout the year, including peas, runner beans, carrots, parsnips, onions, turnips, marrows, Savoy cabbages, Brussel sprouts, purple sprouting broccoli, and of course potatoes. We also grew wheat and barley, plus oats to feed to the horses. There were no tractors. We never ever bought vegetables or fruit to eat ourselves, and certainly no tinned food. We had a few fruit tress – apple, pears, plums and cherries. We never lost much fruit to the birds, unlike in country New South Wales where I now live. The climate was not suitable for oranges or tropical fruits. We bottled fruit for the winter in Kilner jars. Bramley cooking apples were stored in the attic. We always had plenty of fresh farm eggs. Cockerels (roosters) were fattened up for the family dinner, always in the middle of the day.

Preserving pears in Kilner jars for winter eating

Butcher’s meat, bread, milk, newspaper and mail were all delivered to most houses, even in the depths of the country. Groceries were delivered every Friday afternoon and spare eggs taken in part-exchange. We had a roast dinner on Sundays, cold meat on Mondays (washing day) and stew on Tuesdays and Wednesdays (drying and ironing days). We occasionally had rabbit stew or pigeon pie if someone had been lucky with a gun. We had a flourishing garden growing ‘tasty’ vegetables for home consumption, well enriched with horse manure from the dunghill. We saved all our own seeds for the following season. Always fish to eat on Fridays, when we got home from shopping. Fresh fish was sometimes delivered from the nearby fishing port of Brightlingsea. Probably sausages and mash for Saturday dinner. I doubt whether people in towns ate as nutritiously as we did, what with the low wages and high unemployment during the Great Depression.

Groceries were delivered to houses in the countryside in the 1930s

Story #3: Recreation in the 1930s

The games kids played in the 1930s were simple and very physical by today’s standards. There were no computers or videos in those days. Besides ball games, there was hide-and-seek and a tracking game with chalk arrows around the farm. Conkers was a game boys played using horse chestnuts threaded onto a string – the goal being to knock a rival conker off its string without your conker being knocked off its string in a conker ‘fight’. I have tried to introduce conkers to our grandchildren in Australia, but the game has never really caught on. Marbles was played for ‘keeps’ (meaning that the winner kept the marbles) and occasionally there was a craze for collecting cigarette cards. Almost no women smoked in those days, but nearly all the men did, egged on by kids eager to complete a set of interesting cigarette cards featuring such things as express trains or butterflies. Girls played hopscotch and elaborate games with skipping ropes and hoops. We played numerous card games and board games like Ludo in the evenings. We read a lot.

Playing with conkers (left) and marbles (right)

The grown-ups played party games too. There was a sedate action game called ‘Queen Ann’s dead’, much loved by my Grandma. The game dates from Victorian times, if not earlier. In this game, you sat in a circle. A person said to her neighbour ‘Queen Ann’s dead’, and was asked in reply ‘How did she die,’ and was told ‘with her arm say I.’ The arm was then waved about by the first person and everyone had to do the same. The second person then asked her neighbour the same question and invented a suitable death, probably in the leg. And so on until the party erupted in chaotic exhaustion and adjourned for refreshments.

Charades was an acting game that included a two-syllable word that the audience had to guess. This is quite different from American charades, where a word is mimed letter by letter. ‘Murder in the dark’ was popular too. There was much singing round the piano at Christmas time, when all the family, including cousins and great aunts, would congregate at the farm, some to stay the night.

In a game of charades, a two syllable word (e.g. handshake) is being enacted and spoken by the players

The younger grown-ups in our family played tennis in the long summer evenings. They laboriously mowed the grass in the front meadow with an ancient push mower and gave the clippings to the fowls (chickens). They erected posts and wire netting screens around the courts and a fence to keep the cart horses away from the tasty grass. Soon a tennis club sprang up, plus plenty of boys and girls to search for lost balls. Field hockey was the most popular winter field game in our family.

We also had a lot of fun with our domestic animals. The family dog was a cross-bred Irish setter that lived to a ripe old age and was known affectionately as Brother Tim. The family cat was named Darby Dit (Darby kitty). He was out of favour at one time when he ate our pet mice that had been let out while their smelly cage got a scrub. Wilfred was a long-haired white rabbit that didn’t like being cooped up in a rabbit hutch. He was allowed to range freely around the farm with the wild rabbits and was only shut up at night. One morning, he didn’t want to get out of bed, and we found that he had made a nice nest of white fur. You see, he wasn’t a boy rabbit at all and soon ‘she’ had a family of baby rabbits to feed. Well, they all lived in the hutch for a time, but when they grew older they drifted away and went to live with the wild rabbits. They were easy to spot because they had patches of white on them. Long after Wilfred died, no-one was allowed to shoot any rabbit with a white patch on it.

Wilfred’s offspring had white patches of fur

Story #4: Farming in England in the 1930s

We had two cart horses, Tom and Deppa, on our farm in the east of England in the 1930s. Tom was in residence long before I was born. Deppa came later, in foal as it turned out, so we were a three-horse family for a time.

The family in 1931: Grandad, Deppa, me, my mother, Auntie Mil, Auntie Belle and Grandma

It was fun to ride around the farm in a horse and cart, picking up vegetables and so forth. We fattened up beef cattle for a while, to eat up some of the crops that remained unsold in the 1930s during the Great Depression when millions of people in the Western world were out of work. Many factories were closed because their products – like our good fresh farm produce – could not be sold. Truckloads of lovely fresh vegetables were sent in sacks to the London markets, only to be tipped out to rot. Not only did the farmer have to pay for the cartage but he didn’t even get his empty sacks returned! On our farm, we cut our losses by fattening up yearling cattle – extra meat to sell and for us to eat. A useful by-product was a pile of lovely cow dung which was added to a vast dunghill (called a dungle in Essex) in full view of the kitchen window. The hens used to scatter the juicy bits all over the place.

A dungle (dunghill) viewed out of the kitchen window

Sometimes we had two pigs to fatten up, then we feasted on pork before it turned rancid. There was no fridge. Brawn was made from the pigs’ brains and the children were expected to help pick out all the little bones. Hams were hung up in the living room to cure for months on end and they gave the whole house a lovely, homely smell. From time to time, one of my girl cousins came to stay. One day, we were sent out with some stale bread to feed the pigs. We dropped it in their run and a rooster fluttered in to get his share. But not for long. The pigs gobbled him up, feathers, beak and all – not a trace was left!

One of the delights of living in the countryside is to gather wild food, called bush tucker in Australia. In season, we used to pick blackberries, mushrooms and chestnuts. We still do! ’Nutting’ was an exciting adventure for kids in the autumn, with the younger grown-ups being aided by enthusiastic juveniles, all wearing leather gloves. We used to tramp around the local woods that adjoined our Wood Field and break open the prickly green cases to get at the nuts . We roasted them on a shovel over an open fire in the living room. Delicious! Thirty years ago, I planted several chestnut trees at our place in Kangaroo Valley and we now have a plentiful supply of nuts at Easter time. A Swiss-born neighbour of ours takes them to roast on a stall near the ‘Friendly Inn’, so Australians too can be introduced to the delights of freshly roasted chestnuts.

Gathering chestnuts wearing gloves for protection from the prickly outer casing

Story #5: Life with my Grandad in England in the 1930s.

Sometimes, my Grandad would take me with him to our Wood Field in the springtime to shoot wood pigeons. The birds were a real pest because they pulled up the sprouting seeds to eat. We used to make a hide of branches at the edge of the wood where we could wait unseen in our cubby until the birds came to feed on the young plants. We scattered pieces of bread to attract them. I was about seven years old. When Grandad shot a pigeon, he would prop it up to look as if it were feeding, so as to encourage the other pigeons to think they were safe to feed. Sometimes we bagged quite a few birds to take home for my Grandma to cook. My job was to carry home the booty. More delicious bush tucker, but only after the feathers were carefully plucked. Of course, there could be quite a long wait in the hide for the birds to settle, and that is when Grandad used to tell me stories about his own childhood. Here’s one.

Hunting pigeons from a hide in the wood

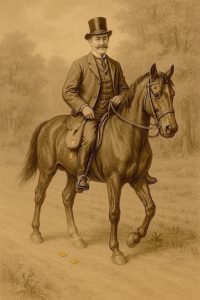

When he was a boy, back in the 1880s, he and his younger brother were sent to help a neighbouring farmer to scare off the rooks. Their job was to scare off these big black birds in the crow family from eating the young turnip plants. The boys were expected to work all day and were paid sixpence each (3p or about 5¢). The day seemed endless in the early English summer. When it was getting dark and the rooks had gone off to roost in their rookery, the boys walked home along a dirt road. Lying in the dust, they saw a big brown penny. Then another, then another, then a halfpenny and once they found a shiny silver sixpence. When they reached home, they had collected over five shillings (about 25p or 50¢). In the morning, their mother sent them to give the money to the village policeman, which they did. Some time later, the owner of the money sent them a reward, sixpence each, for being so honest. So the boys eventually received a whole shilling each for that day’s ‘work’. Grandad heard later that the man with the money had a hole in his pocket. He had been riding his horse, jogging along the country roads. Some people even found gold coins, sovereigns and half-sovereigns, so the man on the horse must have been very rich.

Wealthy gentleman on horseback with a hole in his pocket

I suppose Grandad told me this story to teach me a lesson about honesty.

On Sunday mornings, Grandad would walk around the farm with his dog Tim, to plan the work for the coming week. My cousin David and I used to go with him occasionally, if we were allowed. This was great fun, because there were always interesting things to see and do, like bonfiring when the hedges and ditches had been cleared. Grandad would light the first bonfire with a single match, then carry a forkful of burning grass to light the next fire, and so on down the row. Then we would go back and scatter the ashes to fertilise the soil ready for the next crop. Sometimes we found turnips or carrots that were ready to eat and Grandad would peel one for us with his pocket knife. We always ended up at the ‘Plough and Ship’ public house near the railway station. (Both are pulled down now.) Grandad was fond of his beer and would send us home with a tuppenny packet of Smith’s potato crisps. We always gave Brother Tim (the dog) a share. Grandad would stay on with his mates and play ha’penny nap (a gambling game with playing cards). He was invariably late home for Sunday dinner, much to the disgust of Grandma.

Grandad used to build us a massive bonfire for Guy Fawkes’ Night on 5th November each year. This is still a popular celebration in England, but as November is in the middle of the bushfire season in NSW,, we celebrate Cracker Night in July instead, In the 1930s. the grown-ups would help the kids make a guy to burn on the bonfire. We saved up our pocket money for fireworks and an uncle would bring rockets and bangers. It is no surprise that we are a family of pyromaniacs. During the war, we used to make our own fireworks.

Guy Fawkes’ Night bonfire

Story #6: Family Life in the 1930s.

Grandma took my cousins and me with her to church on most Sunday mornings and sometimes the whole family went. Well, nearly all. Someone, usually my mother, would stay at home to cook the Sunday dinner. I would be gently nudged along the family pew to sit next to the verger, who answered all the responses in a very loud voice and sucked strong peppermints to hide his bad breath. My mother was keener on the pastoral side of church life, and invariably helped decorate the church at Easter and Christmas. That was fun. My cousins and I would be sent into the woods nearby to gather primroses in springtime to decorate the font, where we all had been christened. The church building hasn’t changed much in 900 years. Services today are still much the same as when I was a kid – except for the verger.

Picking primroses in an English wood

Grandma used to tell us stories, usually about the family. About her sister Alice who died of typhoid aged three in the 1880s; or her brother Ernie who was killed in 1915 at Gaza in Palestine fighting the Turks in the First World War, or the two Australian cousins who served in Flanders and visited the family while on leave later in the war, or Grandad’s cousin who came from Salt Lake City as a Mormon missionary after the war. Grandma said the missionary looked very much like Grandad but was not so handsome!

As I grew older, I was able to do more jobs around the farm, especially at harvest time. Firstly, the crop of wheat, oats or barley was cut with a scythe around the edge of the field and raked and bound into sheathes by twisting a few strands of the stalks to form a band. Then the horse-drawn binder went clockwise around the field to cut the crop and bind sheathes mechanically with twine. When only an ‘island’ of standing crop was left in the middle of the field, rabbits would sometimes try to escape, and spectators would try to club them or shoot them to take home the meat for dinner. Then we stood up the sheaves in rows of stooks to dry.

Raking and drying grain crops in the 1930s

A few days later, when completely dry, the sheathes were carted and stacked temporarily near the stables and covered with a canvas cloth to keep out the rain. All the grown-ups in the family could help with this work. A few weeks later, a threshing machine pulled by a steam engine would come to the farm for a day to thresh and bag up the grain, make a permanent straw stack and chop up chaff for the horses to eat. That was the most exciting time in the farming year, at least as far as kids were concerned. Harvesting was very labour intensive in the 1930s, but Grandad said that he could remember when binders and threshing machines first came into general use in the 1890s. Before that, all harvesting was done with scythes and sickles. Nowadays, harvesting is usually done with a single combine harvester that harvests (cuts) and processes grain crops in the one machine.

Threshing cereal crops to separate the grain from the straw

In the 1930s, there were other jobs through the farm year when kids could help, especially at hay-making time. That was a lot of fun too, especially the stacking. Different crops were harvested all through the year and some vegetables such as runner beans were washed in big wooden tubs sited close to the pump by the kitchen door. Pea picking was done by casual labour at sixpence a bag. Kids could earn precious pocket money this way. We also used to feed the chooks and gather the eggs. When a hen went broody and made a secret nest in the stinging nettles, it was the kids’ job to track her down and retrieve the clutch of eggs.

My life on the farm came to an abrupt end in 1938 when I was nine years old. My mother told me that she was going to marry again. She and my new father took me to live with them in a poky upstairs flat in outer London. The contrast from our lovely farm was stark, but I’m glad to say that I was allowed to go back home to the family farm in all the school holidays. So my idyllic life on the farm continued intermittently right up to the end of the war, when the farm was sold. Living in Kangaroo Valley has allowed me to re-experience many of the delightful activities that I remember from my childhood and has also provided similar opportunities for my 4 children, 12 grandchildren and 13 great-grandchildren. What a lovely life I have had!

The family in 2023: Anne, Peter, me, Andy and Paul